Progressive Overloading: A Framework for Building High Performers

I’ve had the pleasure of working with a lot of new grads and early careerists throughout my career. From my years in HR, to scaling BPO operations, to product and product ops, and now. Sometimes by force, sometimes by choice. Over time, I just got better at it.

As I progressed, I realized it’s not a common skill set. Too often I’ve met brilliant individual contributors who took on team manager roles for the first time in their 30s — and then eventually get frustrated. Even more often, I’ve heard the excuse of a “generational gap.” That’s lazy. The real issue is lack of skill and experience in handling high-performing early careerists.

This post is about progressive overloading — a framework I’ve used to harness talent, accelerate development, and build a clear, shared path to hard, meaningful work. It’s a distillation of what has worked (and what hasn’t) across BPOs, startups, and now at Uber over the past decade.

What Progressive Overloading Is

The idea comes from strength training. You don’t start by lifting your max weight. You start small, perfect form, then add load. Skip progression and you get injured. Go too slow and you plateau.

Talent development is the same. You systematically increase workload and complexity to build capability. Capability is many things: capacity to work more, handle stress, manage multiple projects. You push to the limit, then further.

It’s not throwing people into complexity hoping they’ll swim. And it’s not underutilizing them just to keep stress low.

Pressure without progression creates burnout or failure.

The point isn’t just to work harder. It’s controlled stress that builds both competence and confidence.

If you throw people into complexity too early, they’ll think they’re not cut out for it. If you scale volume first, they realize they can handle more. That mindset shift is the foundation.

The Basics: Complexity/Time Matrix

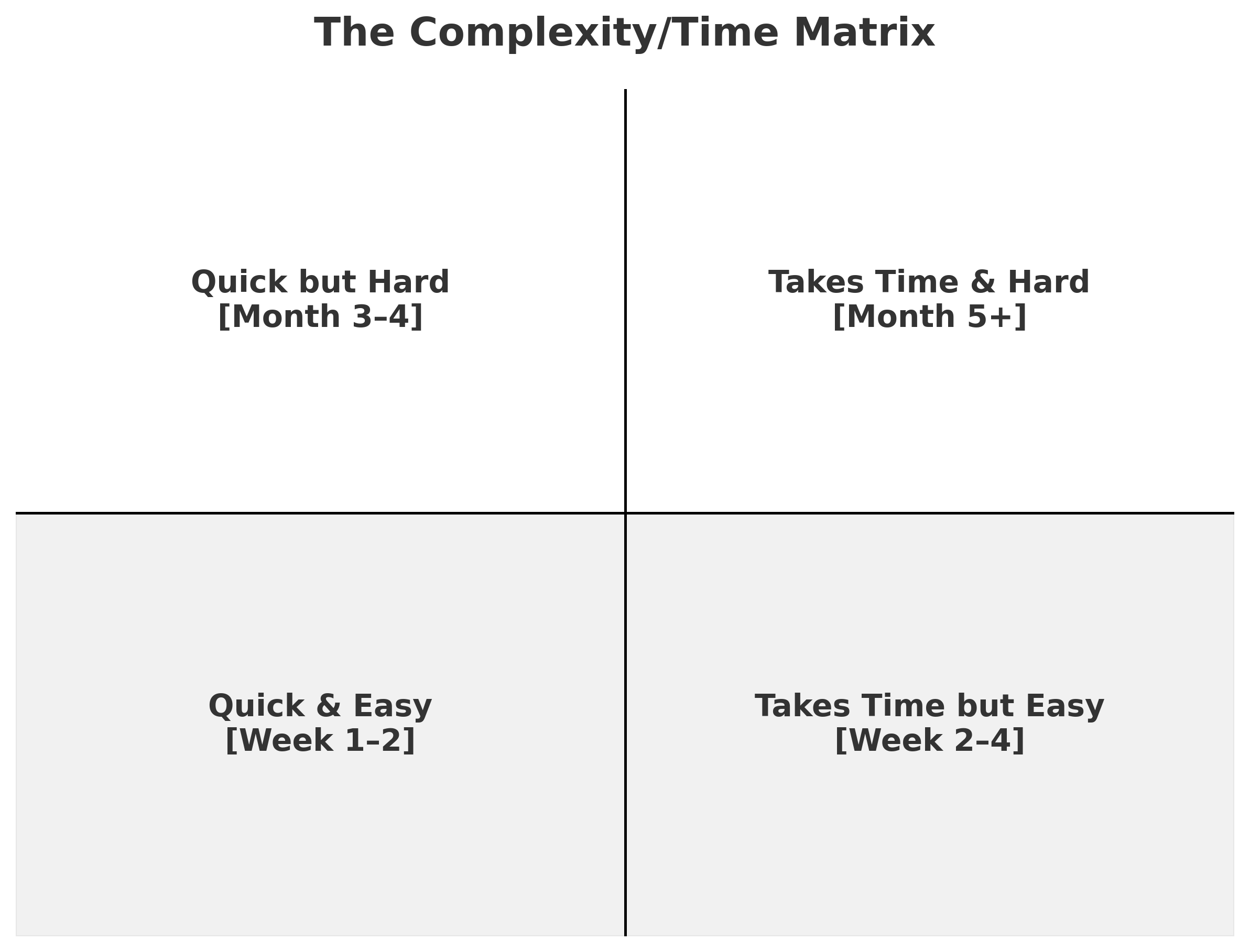

I look at every piece of work as it can be mapped on two dimensions: how complex it is (knowledge and skills required) and how long it takes to complete. This creates four distinct quadrants:

The Four Quadrants

Quick & Easy (Under 30 minutes, low complexity)

Daily check-ins and status updates

Scheduling and calendar management

Basic ticket reviews

Simple data entry

Routine communications

Takes Time but Easy (Hours to days, low complexity)

Research and documentation

Learning new tools through tutorials

Creating basic reports from templates

Attending and taking notes in meetings

Process documentation

Quick but Hard (Under 30 minutes, high complexity)

Stakeholder decisions under pressure

Complex troubleshooting

Emergency response

Executive introductions

Conflict resolution

Takes Time and Hard (Days to weeks, high complexity)

Strategic project planning

Multi-team initiatives

System architecture decisions

Building new frameworks

Leading organizational change

The Critical Rule

Only overload the easy quadrants initially. This is where most development programs fail. They mix complexity and volume from day one, creating stress without learning.

Tasks can be mapped into two dimensions

The shaded area is your safe overload zone in the first few weeks. Stay there until the person proves consistent capacity.

Way back when I was leading Product, I made the mistake of giving Ron, a new grad designer, complex UX challenges right away — research, architecture, interaction design. She was talented but not ready. It led to a lot of frustrations on both ends, eventually culminating to him resigning from the team.

In contrast, at Uber, when Kat joined me on a complex project, I started her with basic tasks. She overdelivered immediately. That gave me the confidence to scale her workload fast — and soon she was producing work that delighted stakeholders and impacted thousands.

Ron didn’t fail because he lacked talent. He failed because I skipped the progression.

The Three Pillars

1. True Alignment

This only works with genuine alignment between manager and employee. Not words, actions.

Do they actually want growth, or just say it?

Do they show it in how they work — staying late to get something right, asking for feedback, implementing suggestions?

Or do they avoid discomfort, make excuses, and deflect feedback?

Self-awareness is non-negotiable. People need to know their current capacity and accept it before pushing further.

The alignment talk happens day one:

“This program will stress you. You’ll be frustrated. That’s the point. We’re testing limits so you can break through them. Stress and negative emotions come with it — and that’s how you build resilience. Weekly check-ins are mandatory. You can ask for less. Failure is acceptable. Not growing isn’t.”

Some light up at that. Others hesitate. Both reactions are fine — what matters is honesty about fit.

2. Volume Before Complexity

New grads don’t know work stress. School stress has clear endpoints. Work stress doesn’t. It’s ongoing, ambiguous, and messy.

Building stress tolerance is the goal. Like training for a marathon, you don’t start at 26 miles. You build volume first.

Regina is a great example. Her strengths showed early — communication, project instincts, hunger for impact. Week one: multiple simple tasks. Week four: entire workstreams of simple tasks. Month two: add complexity.

One year out of college, she was presenting solutions to thousands across Uber — things senior managers weren’t doing. Because she built capacity through volume first.

Contrast Denise from my BPO days. Nineteen, no degree, starting as a call center agent. She began with volume too — scheduling, reports, team comms. As these became automatic, complexity increased. Training design. Team management. Eventually running operations. It took longer, but the progression was the same: volume built capacity, capacity enabled complexity.

3. Weekly Calibration

Weekly check-ins aren’t status updates. They’re developmental checkpoints.

Normalize struggle: “This stress means you’re growing.”

Calibrate load: Watch for quality dips, slow responses, energy drain.

Recognize growth: “That report took three hours last month — now it’s thirty minutes.”

Adjust trajectory: Based on actual capacity, not assumptions.

Mia’s story shows what happens without this. Brilliant new grad, strong start, but we lost discipline on check-ins. Stress compounded, signs were missed, she disengaged, and eventually left. Not because the framework failed — but because we failed to calibrate.

The line between growth and burnout is thin — and you only catch it if you’re watching closely.

Not Everyone Should Do This

Progressive overloading isn’t for everyone. About 30% need something else. That’s not bad. It’s just fit.

Some thrive on one complex project instead of juggling multiple simple ones. Some need clearer structure. Some need validation at every step.

You know it’s not working when check-ins feel like therapy with no progress. When stress leads to paralysis. When someone says they want the challenge but consistently avoids the work.

Implementation at Scale

At Uber, I’ve run this with Product Ops in CommOps, where new grads handle multi-regional problems. We also use it to ramp SOAR trainees fast.

Worth noting: this has been remote for five years. Weekly check-ins on video. Distributed work. Growth and stress are the same. Remote even helps: calendars are tighter, documentation clearer, people open up more at home.

At LOKAL, this is core to how we operate. We hire brilliant new grads and drop them into complex client projects. CJ and RK have run this across teams, adapting it to environments with multiple stakeholders. As long as weekly calibration and volume-before-complexity hold, it works.

Why Most Managers Won’t Do This

It’s easier to throw people in the deep end and blame them for sinking. Or go slow and blame them for not progressing. Progressive overloading demands active, constant management.

The Emotional Labor

You’re pushing people through discomfort daily. Having hard conversations weekly. Reading subtle signals. And you own it if they break. That exhausts managers who aren’t prepared.

A senior manager once told me: “Your approach works for high performers, but some need more hand-holding.” They were partly right. Everyone needs support. The framework gives structure, not hand-holding. Big difference.

The Discipline

Check-ins can’t skip when busy. Load calibration can’t pause. Growth talks can’t wait for next quarter. Most orgs don’t lack good people — they lack managerial discipline.

The Balance

Blaming generations is easier. “Gen Z doesn’t want to work hard.” “Millennials want trophies.” Lazy excuses. Every generation can grow if given the right framework.

The balance is tough — push hard without breaking people. Most managers miss it.

The Payoff

The business results are obvious — faster delivery, stronger output, more innovation.

But the numbers aren’t what stick with you. What matters is the people — and how they change.

Regina doesn’t just present — she knows she belongs. Denise doesn’t just run operations — she knows she can handle what’s next. Kat doesn’t just manage projects — she hunts them.

They walk away with stress tolerance, resilience, self-awareness, work metabolism, and real confidence.

The Compound Effect

People who go through this become force multipliers. They handle more, mentor others, raise the bar. One Regina creates space for three more. One Denise builds an entire org. Over years, that compounds into transformation at scale.

Why This Matters to Me

From HR to BPOs to Uber, I’ve worked with new grads. It’s not just about metrics — it’s about unlocking potential.

Every Denise who could’ve stayed a call center agent. Every Regina who might have been stuck on basic tasks. Every Mia where I learned what I did wrong.

Progressive overloading isn’t just a framework. It’s how I see development: most people are capable of more than even they believe — if you apply the right kind of pressure, systematically, with someone who actually cares.

After a decade, I’m still learning. Still adjusting. I still get surprised sometimes by how far people can go when you do this right.

It’s hard. On managers and employees. But once you’ve seen what people are capable of with the right pressure and support, you know why it’s worth it.